Who Dies First? Conan the Barbarian vs. The Bloody Nine

Fantasy writers, learn how to keep your fight scenes sharp with two classic examples of sword and sorcery

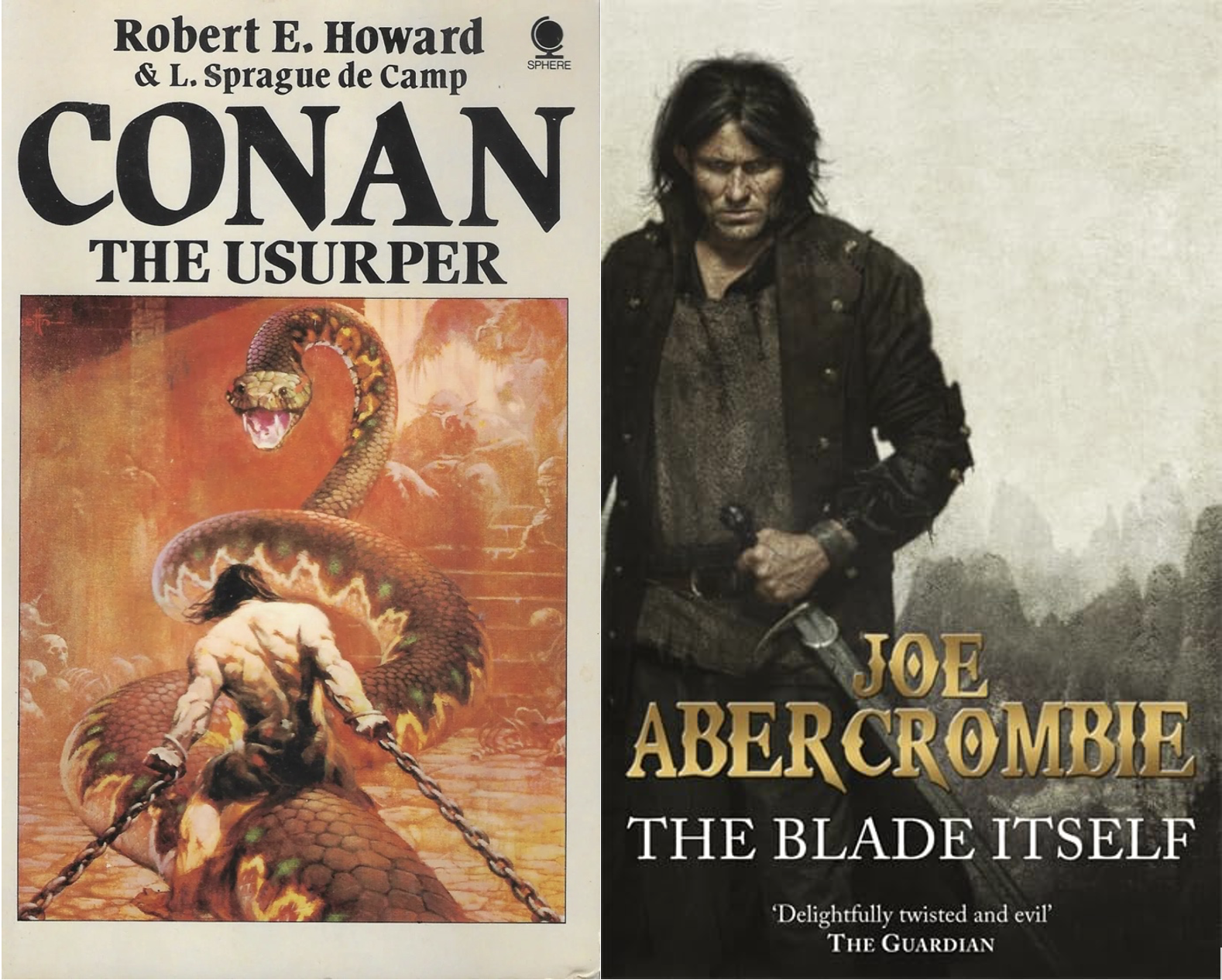

Conan cover art by Frank Frazetta (Sphere edition, 1989), image sourced from reh.world. The Blade Itself cover art by Chris McGrath

Epic fantasy is what you read when you want to lose yourself in a universe of archetypes strange yet achingly familiar, a chronicle that stakes the restoration of a wounded land upon the courage of the fallible and the powerless, a world rich with fellowships reflecting a panorama of human experience and ambiguity, whose choices petty and foolhardy may nonetheless topple empires, a mythopoetry that measures how we live in accord with eternal chaos, weighing the inevitability of darkness against the hope of healing, often reminding us that even that most inevitable of shadows is not a thing to be feared.

Sword and sorcery, on the other hand, is what you read when you want to see a dude stab a giant scorpion in the face.

Rooted in the pagan epics of Gilgamesh and Achilles, by way of the historical swashbuckler, Victorian dino-fiction, and gothic horror, the fantasy subgenre of sword and sorcery traffics in the thrill of mortal combat. It’s right there in the title: here be the sword to which sorcery shall be put.

It’s fantasy’s action-genre, John Wick with a broadsword. Pure, glorious melodrama, prizing spirit, spice, and the weird imagination.

The genre was born a century ago in the pulps, a medium that catered almost exclusively for marginalised readers, “adolescents, the poorly educated, immigrants, and labourers. […] Their taste for ‘trashy’ reading matter was cause for social concern. Cultural commentators throughout the 1930s and 1940s lamented that the proletariat read little else besides pulp magazines.” (How the Other Half Read: Advertising, Working-Class Readers, and Pulp Magazines, Erin A. Smith, 2000)

Sword and sorcery icons like Robert E. Howard’s Conan reflected the readership, the unbreakable underdog biting back against a conniving political class. The strong male body – prized as a vessel of labour – revolts against its master.

The genre’s scenes of combat express a certain rage, while the sword-wielder’s grace and swagger satisfy a craving for agency and control.

Violence is both a vital component and a core theme. Sometimes gratuitous, often aesthetic, always cathartic, sword and sorcery’s scenes of steel-on-steel struggle are exhilarating, terrifying helter-skelters of life and death, which grip the reader by the guts, tight enough to feel the creak of sinew behind every sword-thrust, an amoral spectacle to appease the lizard brain.

But prose isn’t moviemaking.

Blow-by-blow choreography looks fantastic on-screen, but it’s rigor mortis on the page. Authors who want to get pedantic about Liberi’s Full Iron Gate Guard stance or the merits of a zweihänder over an Iberian montante risk making their fight scenes feel like a visit to the library.

So how do we make swordfights work on the page…?