Blog

Here’s where you’ll find previews of all my current projects, as well as updates on signings and convention appearances.

I also post links to essays that appear on my monthly newsletter Agent of Weird: Exploring the Write Fantastic

Subscribe for FREE to receive an in-depth feature every month, plus access to the AOW archive - a dragon’s horde of writing tips, industry insights, genre guidance and more!

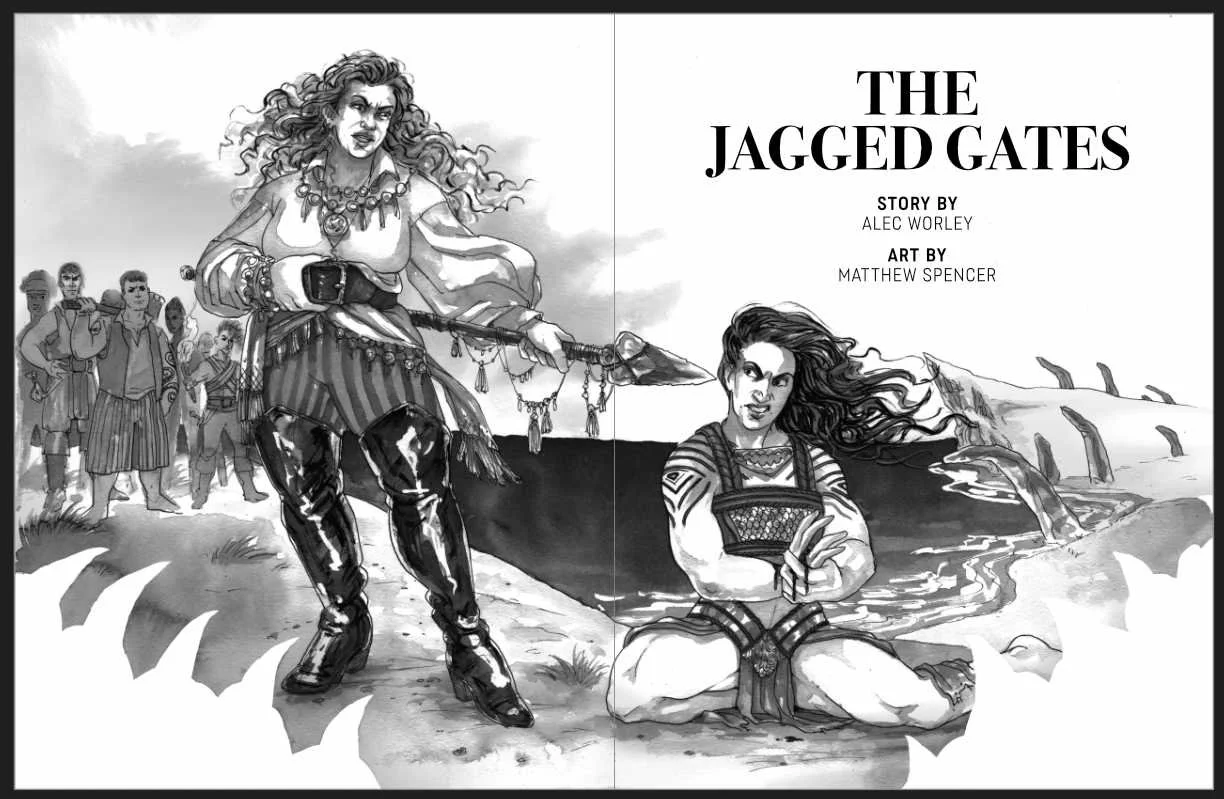

Saving the Writer’s Soul from Work-for-Hire Hell

What creative ownership really means, writing a sword and sorcery tale I can finally call my own, and how it all went wrong when I wasn’t writing for money

Audio of Weird: A Clutch of Christmas Ghost Stories

Snuggle down, drink up and listen in to a read-aloud of ‘Rats’ by M.R. James and ‘Over Before Christmas’ by Alec Worley

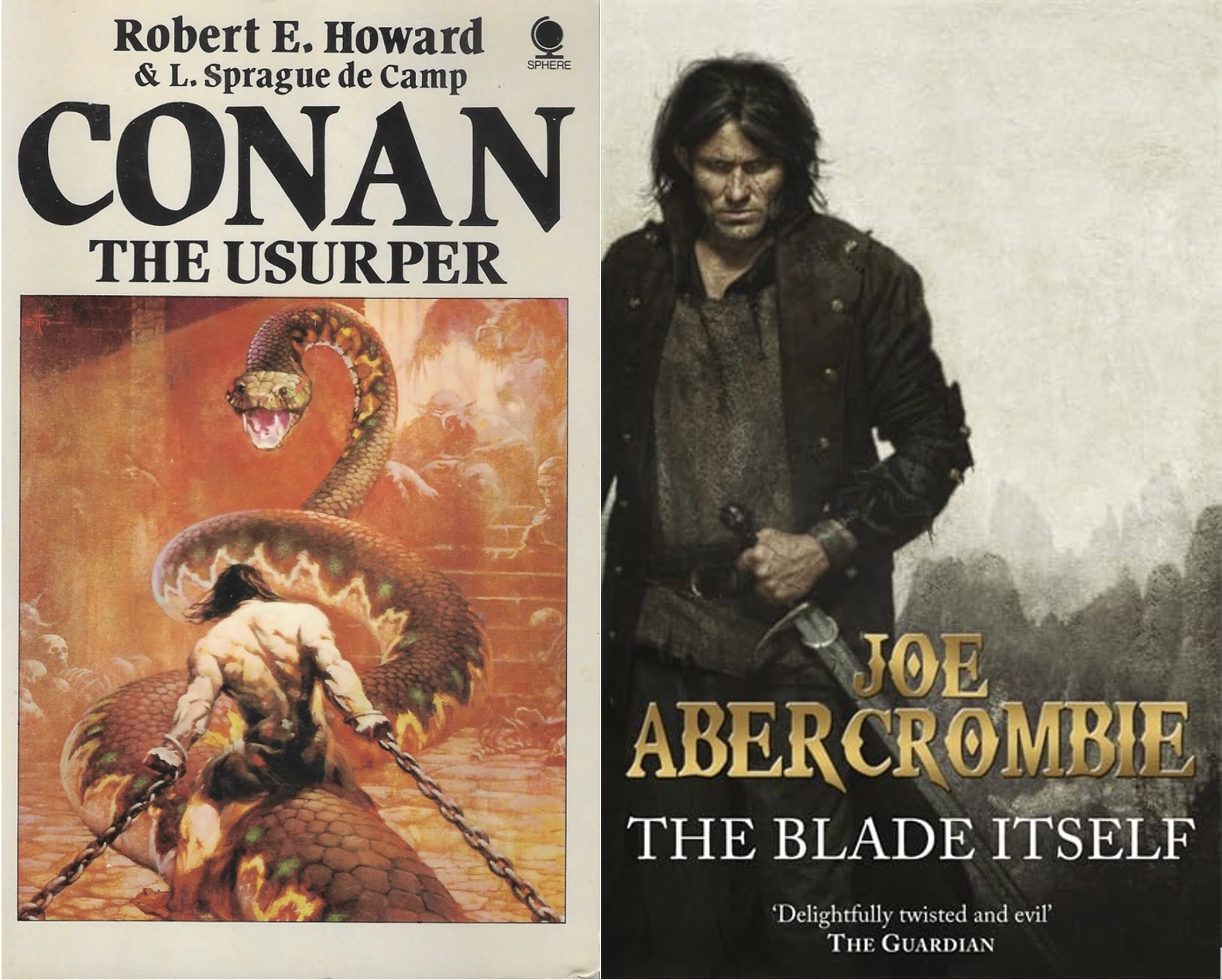

Who Dies First? Conan the Barbarian vs. The Bloody Nine

Fantasy writers, learn how to keep your fight scenes sharp with two classic examples of sword and sorcery

We Need To Stop Being Weird About Theme in Stories

What your story is really saying and why you need to stop saying it

Lessons from Hannibal Lecter: How to Write a Human Monster

Can horror be scary without the supernatural?

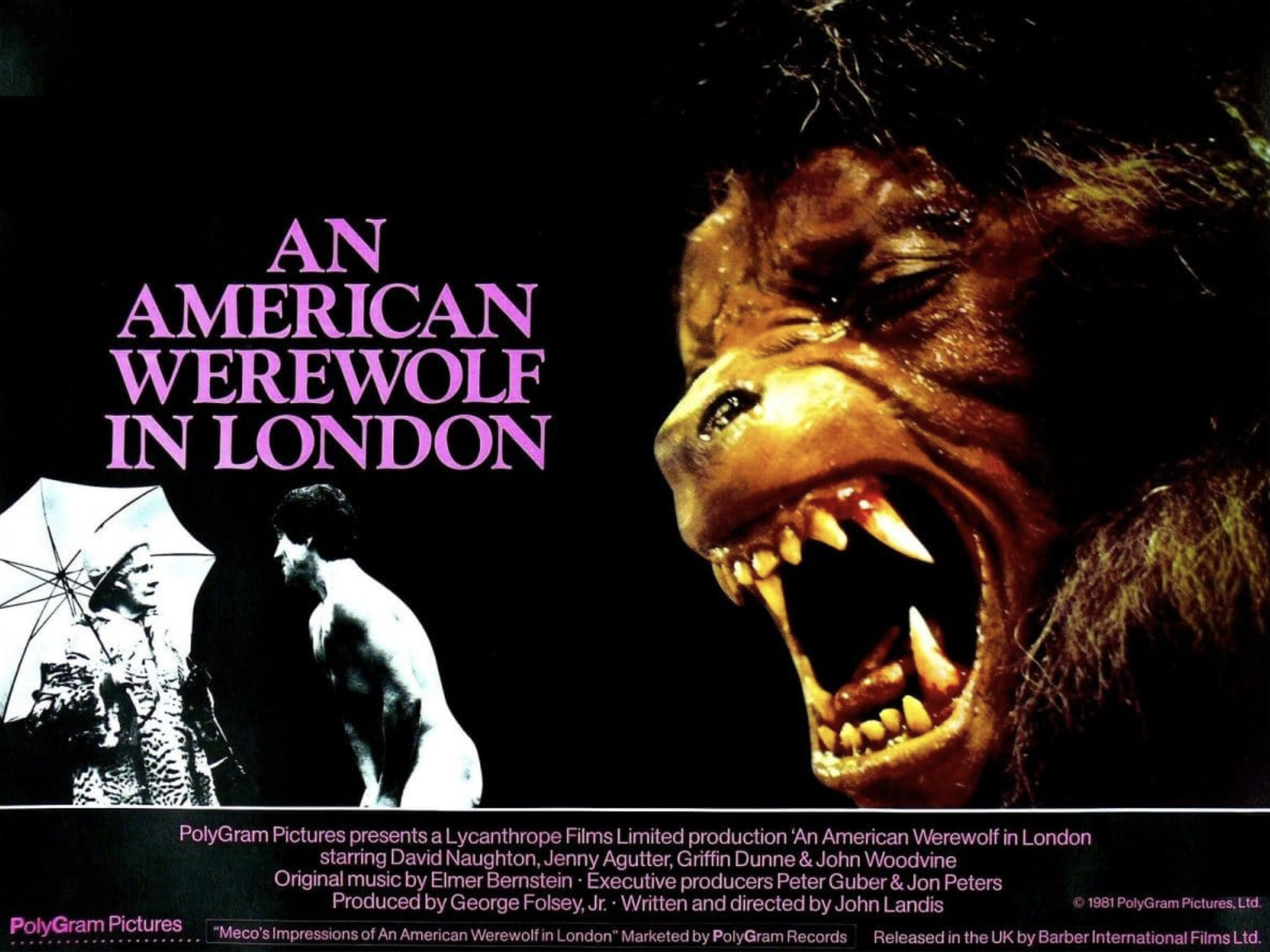

The Best Scene in 'An American Werewolf in London' (1981) Isn't the One You Think

How to write a comedy of terrors

28 Days Later (2002) vs. 28 Weeks Later (2007)

The first two in the ‘28’ trilogy predicted the future and made ‘zombies’ scary again. But the movies’ terrors are more subtle than you think

Science Fiction Double Feature: Who Goes There? (1938), The Thing (1982)

John W. Campbell's classic novella of Golden Age science fiction and John Carpenter's modern horror masterpiece - both absorb new meanings in the age of Covid, identity politics and generative AI

Science Fiction Double Feature: The Crow

The 1989 comic by James O'Barr and the 1994 movie starring Brandon Lee share the same melancholy heart, though it beats in very different ways

Review: Starve Acre (Andrew Michael Hurley, 2019)

This bleak and atmospheric folk horror novel unearths new horrors in old haunts

Science Fiction Double Feature: Planet of the Vampires (1965), It! The Terror From Beyond Space (1958)

Did these drive-in classics really inspire the 'Alien' franchise?